The Barkey family in Tangier, Morocco, circa 1945. Courtesy of Cynthia Flash Hemphill.

Four thick spiral binders filled with yellowed letters–primarily in Ladino–and official documents: this was the trove of material that Bellevue resident Cynthia Flash Hemphill shared with us shortly after the initiation of the Sephardic Studies Program at the University of Washington a few years ago. The cache of documents narrates the unlikely and dramatic escape of Cynthia’s mother, Claire Barkey, and her family, from the island of Rhodes to Seattle, via Tangier, amidst World War II. Following several years of hard work, the documents have been arranged, translated into English, introduced, and now self-published–available on Amazon.

The story of the Barkey family joins Ty Alhadeff’s recent piece, Sephardic Seattle’s Refugee Rabbi, by serving as another example of the resonance of the plight of refugees during World War II and those today. The following is the text of the A Hug from Afar‘s Forward by Professor Devin E. Naar, the Chair of the UW Sephardic Studies Program, which is proud to have helped digitize and preserve all of the original documents from those four binders:

A Hug from Afar is not only one family’s immigration story. Through the unusually rich collection of letters and documents assembled and/or translated here, A Hug from Afar gives voice to a now lost Jewish community on the verge of annihilation, to a Jewish family seeking asylum, and to one young woman who initiated a thread of correspondence with relatives in the United States that would ultimately solidify her family’s escape from the Nazis.

The story itself is not only captivating and powerful on its own, but is also of great historical and cultural significance. Too seldom do we have access to the perspectives of women in history, even fewer with regard to young women, and very few when it comes to the Sephardic Jewish world. While we know of Anne Frank and her diary, we have almost no sources composed by Sephardic Jewish girls or young women describing their experiences regarding the rise of fascism and the onset of the Second World War. While not a diary and not focused as much on the period of the war itself, Claire Barkey’s letters, which form the first part of the present book, nonetheless offer the reader a glimpse into a young woman’s world on the cusp of unimaginable rupture and impending doom.

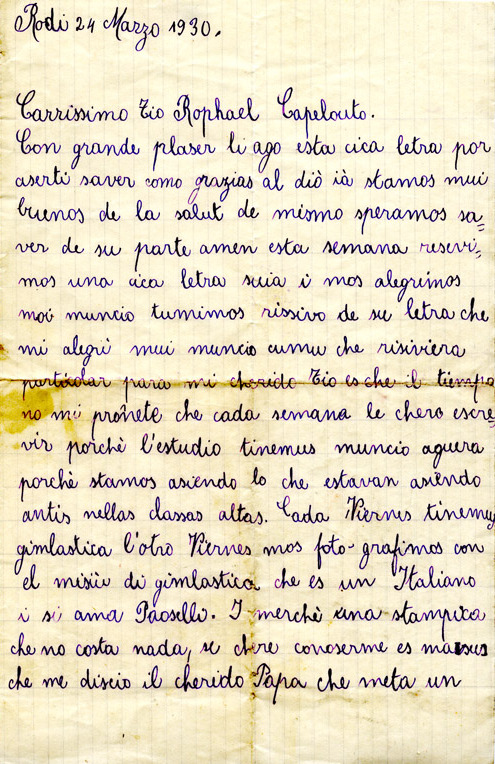

A Ladino letter written by nine-year-old Claire Barkey on the island of Rhodes to her uncle Raphael Capeluto in Seattle. Notice her use of Italian-style orthography, a clear influence of the local cultural environment on the island, then an Italian colony. Dated March 24, 1930.

In the letters that she began writing to her relatives, especially her uncle Raphael Capeluto in Seattle, in 1930, remarkably at age nine, Claire Barkey reveals insights into her everyday experiences and impressions of life on the island of Rhodes and the changes afoot in her society as across the globe. Part of the Ottoman Empire since the 16th century and home to a small but important Jewish community, Rhodes became, in 1912, an Italian colony along with the other Dodecanese islands. These very changes, along with other factors, compelled some of the island’s Jews to seek out new lives elsewhere during the early 20th century. A wide-spanning Rhodesli diaspora emerged with hubs reaching from Brussels to Cape Town, New York to Seattle.

Claire’s initial letters nonetheless reveal the strong imprint of the local cultural milieux. Not only did Claire’s father come from mainland Turkey and hold Turkish citizenship—signifying a continuing link to the old Ottoman world—but Claire’s writing, ostensibly in the local Judeo-Spanish language of the Sephardic Jews, is peppered with vocabulary drawn from the Italian she encountered at school and on the street. She often renders her Judeo-Spanish with Italian spelling conventions. While many of these nuances are unable to be translated, despite the faithful English renderings undertaken by her brother, Morris, they still can be gleaned in the originals, some of which have been reproduced in this book, or explored in more depth in digital form via the Sephardic Studies Program at the University of Washington or in person via the Washington State Jewish Historical Society.

While clearly embedded in the Italian cultural environment that shaped the dynamics of Jewish life on Rhodes during the 1920s and 1930s, Claire and her family experienced a heart-wrenching rupture first with the imposition of fascist laws and ultimately the oncoming Nazi occupation that separated the family, sending members first as refugees to Tangier, Morocco, and then ultimately to be reunited in Seattle with relatives there. The documents offer a rare window into the entire experience, the bureaucratic and diplomatic processes involved in getting the family to Tangier, and then ultimately, after years in limbo, to Seattle in the wake of the war. Along the way, they discover the fate of friends and family they left behind on their native island.

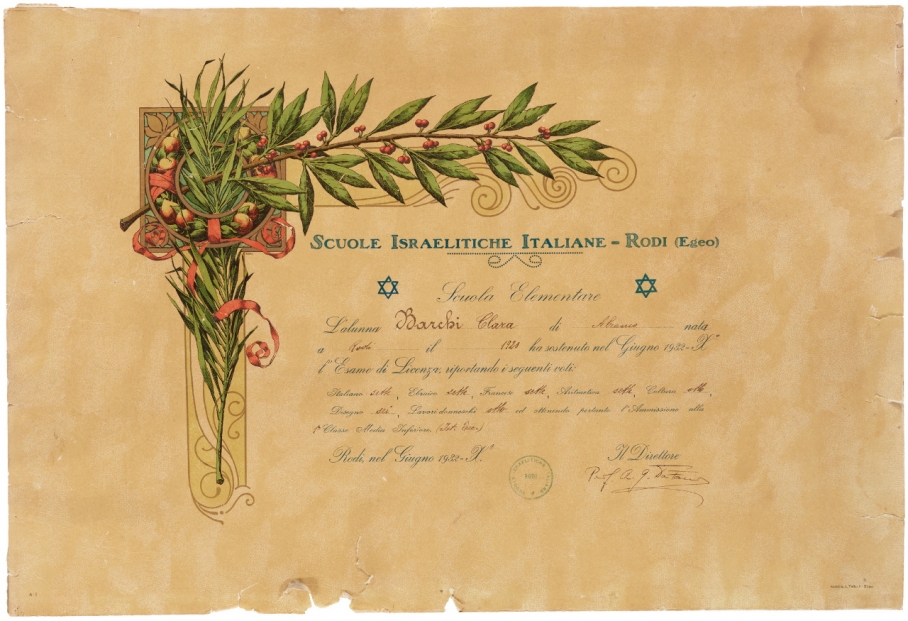

Claire Barkey’s elementary school graduation certificate from the Scuole Israelitiche Italiane, Rhodes, 1934.

It was thanks to the correspondence that young Claire initiated with her uncle in Seattle, well before the onset of the war, that her rescue and that of her family became possible—indeed a reality.

As much as the tale that unfolds in the pages that follow reveals a powerful “hug from afar”—the embrace between relatives stretching from the Aegean Sea to the Puget Sound—it also represents a set of missives from afar, letters from a bygone world, documents that reveal aspirations and anxieties shared by Jews all throughout Europe on the eve of World War II. For every story of a successful escape, like the one documented here, there were many more attempts that never came to fruition.

Finally, as much as A Hug from Afar is a tale of immigrants, it is also a tale of exiles and refugees. Today, in an era in which the plight of refugees preoccupies us anew, the story about Claire and her family revealed in this book gains new vitality and relevance. The members of the family that played a role in bringing their story to light for us in the 21st century should be applauded. They remind us how much we have learned—and how much we haven’t.

Devin E. Naar

Isaac Alhadeff Professor in Sephardic Studies

University of Washington

Clara Bar-abi or Barkey’s letter was no more “ostensibly” in Ladino than the anglo-sefardic transliterations of other Ladino language bits you put up on the Stroum Center web pages. It was perfectly good, every day Ladino of a girl in a Hispanic Jewish family on a Greek island, once owned by Venice, dominated post-war by Italians, who were attacking the Turks who had dominated the Ottoman Empire (Ozmanli Caliphate) which had welcomed them after the Christians of Iberia had rejected them. We should be glad it was not a mix of Hebrew, Arabic, and Roman letters, with French and Spanish orthography as well! Enough other documents have all those alphabets and orthographies scattered on the same page. But Orthography, the spelling system employing a particular set of letters, is not what determines language, as we know from linguistics. What proves its Ladino quality is its absolute consistency in the phonetic and morphological structures of Ladino Spanish — no other dialect of Castillian is similar– whatever spelling she might have chosen, that would not have varied.

Es una parte de mi famya ke se salvo in yindo in America. Mi madre Rosa Capelluto de Rhodes dizya ke tenyamos tyos i primos in Seattle. Aki la prova.

Muestros primos eran, Notrica, Tarica, Menashe, Gattegno, Levy..

El espirito rodesli se mantuvo fuera de Rhodes.Puedeser ke se podrá espanderse de mas

Renaud Souhami